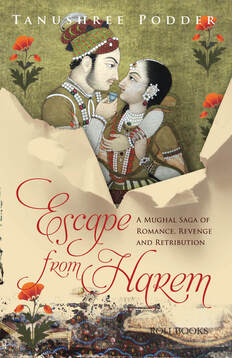

It was a dark, winter night when Zeenat was thrown into the Mughal emperor’s harem to satisfy his lust. Set against the backdrop of Jahangir’s indolence and Shahjahan’s rebellion, Escape from Harem tells the story of her life that changes forever that fateful night. From the harem of Jahangir to Shahjahan’s golden age of architecture and Jahanara’s boudoir, Zeenat’s life is a dizzying roller coaster of events, with moments happy and sad trapped in the quagmire of the imperial zenana. The silken skeins of romance juxtaposed with the coarse threads of passion and aggression recreate the tumultuous period of Mughal history. Traversing the span between circa 1610 and 1650, her story is also a preview of the Mughal culture and way of life.